“OCCIDENTALIS IN STATE”

Did John Muir document “Canadian Timberwolves” in California?

The recent re-establishment of a gray wolf population in the northern part of California is one of the most polarizing and divisive wildlife subjects in recent memory. The average local in the rural northern part of the state already feels under-represented and overlooked, and the highly politicized protection of this species (federally and at the state level) as they re-establish their population here (and remind us all of why they were eradicated in the first place) seems to be either infuriating or worth celebrating, depending on your perspective. It’s either a big win or the end of life as we know it, and no middle ground seems to be welcomed into the conversation.

Debate over whether or not wolves should be tolerated in the state is one thing. It should be a healthy discourse. It’s not, of course. It’s hostile, angry, and short-tempered. One big reason that it’s not a healthy discourse is that both “sides” of the big debate about wolves like to operate with just a little bit of fantasy mixed in with reality. If you celebrate the return of wolves, you gravitate to talking about ecological balance, herd health of prey species, the role of keystone predators in the food web, the restoration of watersheds, etc. You creatively skirt the fact that it’s a vastly different food web than it was at the beginning of the last century, with far less prey available and far more space taken up by people and livestock. If you despise wolves, you lean towards convincing people that they themselves (or their kids!) are in very real danger (in spite of the natural tendency of wolves to avoid humans), you explain that wolves “kill for fun,” and you remind everyone that these wolves that are here now are not the same wolves that were here before. They are a “Canadian Timberwolf.” Bigger, more aggressive, and more drawn to larger game, which gives them a taste for livestock when they can’t find a caribou in Siskiyou, Plumas, or Lassen County.

It is that last point that sent me down a bit of a research rabbit hole, because there should be some facts out there that either prove that statement to be true or false, shouldn’t there? I mean, we know which wolves are here now… but were they in fact never here historically? A lot of folks throw that statement into the conversation as if no thought could have possibly gone into sourcing wolves from Canada to reintroduce into Idaho and Yellowstone in the 90’s. Knowing that wildlife biology doesn’t generally operate on “no thought,” I wanted to learn about the various subspecies of gray wolf, and how crazy it actually is that the “Canadian Timberwolf” is now roaming the woods behind my house. I read DNA studies and various accounts of the actual differences between gray wolf subspecies, but the most interesting thing I found came from none other than John Muir, the famed California naturalist, author, and possibly the greatest student of the wilds of the west in American history.

I hope that this can be digested (and presented) in a way that does not enter into that hostile, angry debate. I am both a rural northern California local, and a big advocate of wild nature. I have friends that worry for their livestock, and friends that celebrate the return of wolves. I am making no attempt to solve that debate here. What I am attempting to do is remove at least one piece of the “fantasy” that makes real conversation impossible. An essay like this could be written about any of the “extreme” statements that either side of the wolf debate leans into (i.e. “Are the wolves really responsible for the recovery of aspen groves in Yellowstone?”), but this one is about the historical possibility that that the “Canadian Timberwolf” once roamed northern California (spoiler alert: John Muir’s journal says it did).

Nubilus, Fuscus, and Occidentalis

The roots of the anger over the “Canadian Timberwolf” lie in the fact that the wolves that have recently made their way into California are descendants of the wolves that were reintroduced into the wilderness of Idaho and Yellowstone National Park in 1995 and 1996. They have come via generations of dispersals and established population groups in Montana, Wyoming, Idaho, Washington, and Oregon. The Yellowstone and Idaho wolves were captured in or near the Mackenzie Valley in Canada (“Mackenzie Valley Wolf” is another name for “Northwestern Wolf, which is another name for “Canadian Timberwolf,” which is another name for the subspecies Canus lupus occidentalis). After much deliberation and consideration, these wolves were the ones chosen to re-inhabit Yellowstone and Idaho. it’s worth noting that the northern Rocky Mountain wolf (Canis lupus irremotus) was the historical resident there. The main difference between the two is that Occidentalis is slightly bigger. As a reminder, the reason we’ve had to make decisions like this is because the extinction of historic resident subspecies was 100% our doing, and collectively, humanity now thinks that was a mistake.

The gray wolf (Canus lupus) has been divided into several subspecies, which have been debated, revised, and adjusted over time. Reasons for subspecies division in species populations can be made because of observable characteristics, diet, location, DNA, or other factors that taxonomists determine warrants a special subgroup. In the case of the gray wolf, there are really three of these historically recognized subspecies that could have possibly been present in the northern part of California, although their actual status as a “subspecies” has been the subject of much debate (side note: the Mexican gray wolf is also understood to have been present once upon a time in the southern part of this very “long” state).

Canis lupus nubilus, the “Great Planes Wolf,” is the subspecies that the majority of scientists consider to be the most likely historical inhabitant of the far northern part of California. These wolves would have migrated into northern California from Nevada in the east. They are generally described as “medium to large”, 60-110 pounds, with varied coats that range from “buff, light gray, or white to black and reddish brown, often with mottled, dark, or silver coloration.” Nubilus as a subspecies is considered to be extinct. A few were held in captivity and bred to prevent total extinction, and their descendants survive in the great lakes region, but mixes of subspecies have happened along the way. Scientists call it “partial recovery,” for all intents and purposes, nubilus is no more.

Canis lupus fuscus is the “Cascade Mountain Wolf.” This subspecies (also considered extinct, also our doing), can be described as “medium to large,” around 80-100 pounds, with a distinctive cinnamon colored or grayish-brown coat. Historically, they are thought to have inhabited Washington, Oregon, and the northern part of California.

And finally, our current resident: Canis lupus occidentalis, the “Canadian Timberwolf” or “Mackenzie Valley wolf” or “Northwestern Wolf.” These guys typically weigh 85–115 pounds (but can get up to 145+ lbs) and stand 30+ inches at the shoulder. Coats can vary widely, with shades of black, gray, tan, and white. Their most distinguishing characteristic other than color is their size. These are the ones you’d call “big” if you had seen any of the others first. The southern extent of their historic range has been considered to be “mountainous regions of the northwestern united states,” putting the northern part of California into that gray area of possibility at the far south of their range. But is there any proof that they were ever here?

It’s worth noting here that In 1995, renowned taxonomist Dr Ron Nowak published a seminal paper completely revising the taxonomy of subspecies for the gray wolf in North America. He essentially concluded that previous scientists had split up Canis lupus into many more subspecies than morphological measurements supported. Until Nowak’s assessment, it was commonly believed that there were 24 different subspecies of gray wolf in North America (reflected in these subspecies I just described). In taxonomy, there are what are called “lumpers” and “splitters.” Splitters believe that minute differences in morphological measurements indicate the need for a new separate subspecies. Lumpers believe that those minute differences are so insignificant that they do not constitute a separate subspecies. Wolf scientists and taxonomists agree today that much “splitting” took place, and that there were historically really only 5 subspecies of gray wolf in North America: Canis lupus arctos (the arctic wolf), Canis lupus baileyii (the Mexican gray wolf), Canis lupus occidentalis (Canadian Rockies wolf/Rockies wolf/Northwest wolf/Western wolf), Canis lupus nubilis (plains wolf) and Canis lupus ligoni (British Columbian coastal wolf). Some scientists think it’s not a useful device at all to try to draw lines on a map and say that this wolf subspecies lived here or that wolf subspecies lived there, recognizing that there can be substantial skull size and shape variation even within any given wolf population. There is even a (extreme “lumping”) scientific argument to be made for one single morphological unit for the gray wolf in all of North America, in spite of differences in appearance and location. Because wolves anywhere largely have the same biology and behavior and fill the same ecological role, a longtime, highly respected wolf biologist, Dr. L. David Mech (pronounced meech), long ago coined the phrase “Canis lupus irregardless” to express this concept.

Enter John Muir

The Cascade mountains extend down into California, an extension of the habitat that stretches south from Washington, through Oregon, and right into the region where wolves are now making a comeback in the Golden State. Mt Lassen is the southernmost Cascade volcano, and slightly north of Lassen is Mt. Shasta. It’s worth noting that the fist confirmed modern wolf pack in the state of California (2015) was the Shasta Pack, and the second (2017) was the Lassen Pack. It is significant to this conversation that occidentalis chose this particular area for their habitat, since it was near Mt. Shasta where John Muir enters this conversation.

No California naturalist needs less of an introduction than John Miuir. A champion of the high Sierra, his name is synonymous with the Yosemite region, and his volumes of writing about the mountains of California and the native flora and fauna have inspired generations of lovers of the outdoors. If you read much John Muir, you quickly become aware that he was constantly traveling, keeping copious notes in journals, which would eventually be consolidated into various writings… books, essays, newspaper articles, magazine submissions… he was constantly documenting all things wild, most of which would become his next published work, the goal being to inspire others into a deeper appreciation of the places and things he documented.

His journals have largely been digitized and are publicly available and keyword searchable through the generous efforts of the University of the Pacific. Having read through most of Muir’s published work, browsing his journals is fascinating because you feel like you are along on the trip that he would later write about in the book you read. You recognize the notes that were taken that wound up in the essay or book, and you also recognize the small things that didn’t make the published account.

I searched the journals for any entries Muir made about wolves in California. He obviously made quite a few notes about wolves in later years during his travels in Alaska, but he did also mention them in his California journals, though not as frequently.

To set the stage, we must understand that Muir spent most of his “California” time in the lower half of the state, specifically in the Yosemite region and south. When documenting the San Gabriel mountains in the southern part of the state, he mentions wolves in passing as one of the residents of the area, although there is no case to be made that he actually saw one:

“…down in the dells are little gardens with lilies & ferns & mosses soft as a kittens paws, Frames not made with hands where dwell the bushy tailed rats & bears & wild cats & deer & foxes & wolves.”

Does this mean he had encounters with wolves in the San Gabriels? No. But it does indicate the possibility that he knew of their presence in the area. His encounters increase the further north we go. At one point in Yosemite in 1873, we have this entry:

“Deer going up Big Meadows. Although ground still mostly snow covered. Wolf Track. Chipmunk at Tuol [Toulomne] Meadows”

The location being confirmed by the Toulomne Meadows line, we have the first documentation from Muir of an actual encounter with wolf sign in California. And for the skeptic, it’s important to note that he had extensive interactions with coyotes, writing about them at length. He often jokingly called them “California wolves,” but was always quick to clarify that Canis latrans was certainly not Canis lupus. As a sheepherder (documented in “My First Summer in the Sierra”) he had several encounters with coyotes attacking sheep. He knew them well. For Muir to write “Wolf Track” with a capital W and capital T, and no tongue-in-cheek reference to “California wolves”… You can rest assured that he saw a wolf track.

For his essay on “The Forests of Oregon,” Muir went back into the records to document man’s efforts to eradicate various predator species in the area immediately north of the Shasta area of California. In his journals from his 1879 and 1880 trips, we find this sobering information noted, and these paragraphs in the resulting essay:

“As early as 1843, while the settlers numbered only a few thousands, and before any sort of government had been organized, they came together and held what they called “a wolf meeting,” at which a committee was appointed to devise means for the destruction of wild animals destructive to tame ones, which committee in due time begged to report as follows: -

It being admitted by all that bears, wolves, panthers, etc., are destructive to the useful animals owned by the settlers of this colony, your committee would submit the following resolutions as the sense of this meeting, by which the community may be governed in carrying on a defensive and destructive war on all such animals: -

Resolved, 1st. – That we deem it expedient for the community to take immediate measures for the destruction of all wolves, panthers, and bears, and such other animals as are known to be destructive to cattle, horses, sheep and hogs.

2d. – That a bounty of fifty cents be paid for the destruction of a small wolf, $3.00 for a large wolf, $1.50 for a lynx, $2.00 for a bear and $5.00 for a panther.”

Is it possible that a “fifty cent wolf” was Canis lupus fuscus, the cascade mountain wolf, and that a $3.00 wolf was Canis lupus occidentalis?

The Shasta Trip

In late 1874, Muir traveled to the Mt. Shasta area. He famously summited the mountain on November 2nd, spending a night near the summit in the warm mud of a sulfur vent to wait out an early season snowstorm (one of the most classically “John Muir” things that John Muir ever did). On November 5th, apparently having recovered from the ordeal, he joined a group of hunters that included Justin Sisson (owner of Sisson’s Station), a hunter named Jerome Fay, and two visitors from the UK named Brown and Hepburn. Their target was the Shasta bighorn sheep. It’s certainly worth noting here that the Shasta bighorn is a subspecies of bighorn that is now extinct (yes, human caused), and is therefore absent as a prey species in the region where our modern wolves hunt.

Muir’s journals from this hunting trip served as the backbone for a series of letters published in the San Francisco Daily Evening Bulletin titled "Shasta Game," published in December 1874. The journals document the hunt as well as all of the flora and fauna that Muir encountered. And on this trip, he encountered wolves. He mentions them several times in his journals, at one point noting that “the sheep fear no predator save the wolves.” At another point after an unsuccessful day he notes “but this day, only wolves were seen.”

And then there are the entries that leapt off of the page as I was researching this topic. First, an account written during this hunt that includes at least a brief description of said wolves:

“There is no lack of wolves yet. Big gray ones as well”

Big gray ones. Not “medium reddish ones”. And does the “as well” indicate that there were also medium reddish ones? Or smaller gray ones? It leaves a lot to the imagination, but only until you get to the “smoking gun” journal entry. Written before the summit climb and before the sheep hunt, just a few days before his memorable night on the summit of Shasta, Muir was sitting along the banks of the McCloud River. Thankfully on this particular journal page, he gives us a date and a location: “Oct 28th 1874 Ferns of the McCloud 2 miles above the confluence with the Pit.” You have to remember that Shasta Lake wasn’t a thing yet, but he was sitting along the McCloud river in a canyon that is now a part of Shasta Lake.

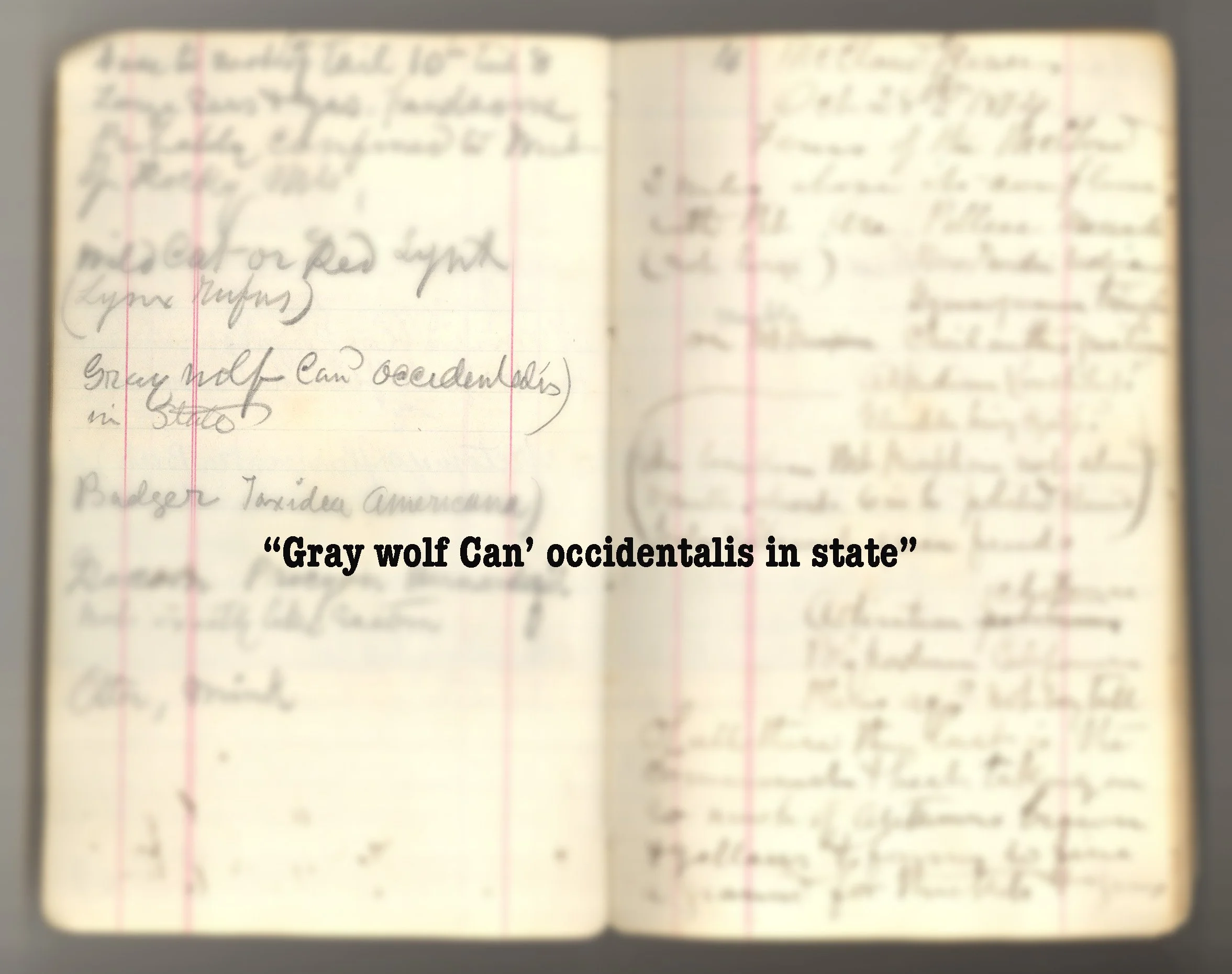

Muir was documenting various species that he had seen in this part of the state, it being his first journey into the area. Undoubtedly he was comparing this volcanic region with his beloved southern Sierra peaks, the work of glaciers being replaced by the work of vulcanism as the Sierra transitioned into the Cascades. A new corner of his beloved state to explore, with new opportunities for discovery and wild education. He notes “Wild Cat or Red Lynx (Lynx rufus).” Bobcats. He notes that the raccoons of the area are “not exactly like eastern” and calls them “Procyon hernandezii Mexican plateau raccoon”. He mentions seeing badger. Otter. Mink. And then, in the middle of these observations, we have this line:

“Gray wolf Can’ occidentalis in state”

The “Can’” is certainly shorthand for Canis lupus. But the very specific “occidentalis in state” is an amazing notation. This is not someone who saw a wolf and didn’t know what he was looking at. This is John Muir. Misidentifying Canis lupus occidentalis for John Muir would be like Michael Jordan accidentally playing with a WNBA sized basketball and not noticing. This wasn’t a post for attention on Facebook, it was merely a notation of a species whose presence in his beloved California was very noteworthy. “Occidentalis in state” is not a phrase that can be taken in more than one way. And when the source is John Muir, the idea that this could be a taxonomy mistake is, in my opinion, laughable. He would go on over the coming weeks to have run-ins with these wolves on the sheep hunt, with this new knowledge of their presence in the state already noted in his journal as he wrote about the “big gray ones.”

So what does this 1874 observation mean for us now? It simply means that the “Canadian Timberwolf” argument doesn’t really hold much water when used as a primary reason for why they shouldn’t be here. Based on Muir’s account, I believe occidentalis was in this part of California. And yes, nubilus and fuscus were probably here too. It was a different time. There were sheep to hunt, people were scarce, wildlife was abundant. For some people, the return of the wolf is a source of hope that a wilderness teeming with wildlife is possible again. But is the return of this apex predator putting the cart before the horse when prey species like the bighorn sheep have been replaced by livestock? Many say yes. Clearly, those are not problems that can be solved in an essay. For now, we have two truths: John Muir, 1874: occidentalis in state. And as of OR7 in 2011 and the Shasta Pack in 2015: occidentalis in state. Canis lupus irregardless.